Meet Jephrin Wong. He is the Deputy Director of Sabah State Fisheries Department in the state of Sabah, Malaysia. He is a man on a mission and that mission is to save mahseer and the rivers they swim in.

I was lucky enough to sit down, share a meal and a very long chat with Jephrin while I was in Sabah. My visit was to try to catch some mahseer from the tropical rainforest rivers, a job made a lot easier thanks to this cheerful man’s vision.

His small stature and giggly chat belies a hard work ethic and empathy for the environment that probably comes from his Chinese heritage.

Before the chicken rendang and rice gets too cold, here’s what we had to talk about…

What is your scientific background, and how did you get involved in fisheries work?

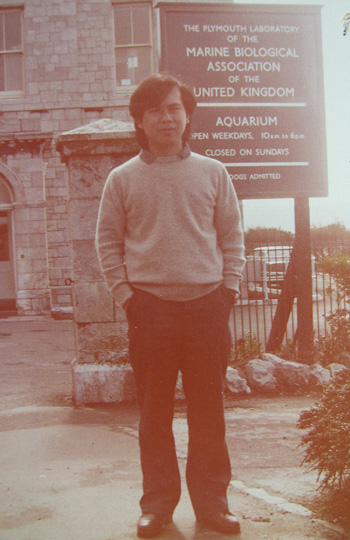

I studied Fishery Science at Institute of Maritime Studies, Plymouth University in the UK (1984-1987). Although it was a freshwater course I was interested in, there are not so many chances to work with freshwater fisheries at Plymouth. Most of the study was related to marine fisheries, fishing gear technology, fishery business, fishery law, weather and climate, oceanography, marine biology and aquatic plants like seaweed. We also had to go to Hull to do some of the research work on fishing gear because they had a Flume Tank facility.

I studied Fishery Science at Institute of Maritime Studies, Plymouth University in the UK (1984-1987). Although it was a freshwater course I was interested in, there are not so many chances to work with freshwater fisheries at Plymouth. Most of the study was related to marine fisheries, fishing gear technology, fishery business, fishery law, weather and climate, oceanography, marine biology and aquatic plants like seaweed. We also had to go to Hull to do some of the research work on fishing gear because they had a Flume Tank facility.

It was 1987 when I finished my degree and came home to Sabah. I continued working for the Fisheries Department, but it was mainly the sea fishery, fishery enforcement and molluscs I was dealing with. After a few years, in fact I think it was in 1997, my boss transferred me to working in the freshwater division.

What were the rivers like in those days?

Many of them had very few fish. There were some remote areas with plenty of local fish like Tor douronensis (blue mahseer) and Tor tambroides (red mahseer), but in many places the fish were being harvested very heavily for eating. It is a tough life for these Kampong (rural village) people. The people there don’t have much money, so they have to eat only what they can grow, pick or harvest locally; fish is the major protein source for these people.

When did you come up with the idea for the river protection scheme?

T hat was around 1998, but we set up the first scheme in 2000. I spent time travelling into the villages, looking at the rivers and seeing how the locals lived. I knew that I had to be involved with them to build trust. I spent time talking with village heads, going to weddings and festivals, just so they would know who I am and be happy to work with me.

hat was around 1998, but we set up the first scheme in 2000. I spent time travelling into the villages, looking at the rivers and seeing how the locals lived. I knew that I had to be involved with them to build trust. I spent time talking with village heads, going to weddings and festivals, just so they would know who I am and be happy to work with me.

Finally, one of the village heads said, ‘you must give support, not just talk’. That made up my mind to do something.

I told my boss what my idea was, but he didn’t think it would work. Many of my friends said ‘you’re crazy’, but I decided to begin my plan.

The Tagal system was introduced in 2000, explain it please.

Tagal means protection in the local language of Sabah. I went to the village of Babagon, not far from Kota Kinabalu, the state capital, and we began the process of saving the fish in the river there.

First, we had to form a committee of the locals to control the scheme. Then, we had to agree a way to police a ban on taking fish from the river at certain times. It has to be a win-win situation, if you just ban fishing of any kind, then the locals will be against you.

I managed to get some funding from both the state government and federal government to spend in the village. We bought them nets to make the fish harvest easier when they were allowed to do it. A hut was built next to the river so the locals would be more comfortable when doing monitoring. We also bought some cool boxes so they could keep the fish in better condition to take to market.

It took two years of meetings and hard work to get the first site running properly. Then we decided if we introduced catch-and-release angling at the site there could be more money going into the local economy. Our next step was to find a way to let the locals have some access to the river, while protecting other parts so visitors could catch fish for a fee.

That’s when you came up with the zoning idea?

Exactly. We said you can fix three zones around the village. A red zone means only catch-and-release fishing is allowed, the fish cannot be harvested from there at all. In the yellow zone, there is harvesting allowed two or three times a year for special occasions. The green zone can be harvested at any time by the local people only.

Exactly. We said you can fix three zones around the village. A red zone means only catch-and-release fishing is allowed, the fish cannot be harvested from there at all. In the yellow zone, there is harvesting allowed two or three times a year for special occasions. The green zone can be harvested at any time by the local people only.

All the fees paid for catch-and-release angling go to the village committee; it makes sense that if they own it, they will protect it. The village committee decide how that money should be spent.

Have there been any problems with the scheme?

Oh yes!

You have to use a few strategies to make it work. These communities are mixed ethnicity: many indigenous communities (Kadazan-Dusun, Bajau, etc), some Sabah Malays, some Chinese, and Malays from the mainland. They don’t always find it easy to work together. By us showing the amount of support they can get from the Fisheries Department, they can put aside their differences and work for the community.

At the sites where angling tourism is possible, we build public toilets. At some of the bigger sites we provide a boat for the Tagal system committee to use to monitor the sites for illegal fishing. In some places there is a lot of river to look after, so we never start a scheme without involving the local police in the committee. The Fisheries Department has an enforcement unit, but in these days of good IT and communication, it is very easy to contact the local police and make sure the protection continues.

Go through the process of getting a new Tagal site operational please.

After the first scheme started it then took two years to start the second one. Now, after 12 years there are more than 500 villages in the river Tagal schemes and more than 200 rivers are being protected. We don’t have to find new sites any more, the success of the scheme means villages now come to us and ask to join. When I started this, I never knew it would be so successful.

So, we visit a site and see how much river has to be protected. In some places it is easier to protect a long piece of river if access is only available through the village. In other places it may just be possible to protect a short stretch and the villagers decide to only use one or two zones, not all three.

Before any new Tagal site can be finished we have to have a ceremony involving the Chief Minister of Sabah. We want it to be a celebration, like a wedding, so everyone knows that such a river is protected under the Tagal system scheme and everybody is happy.

The Fisheries Department pays for signs to put up on the river showing it is a Tagal site and then we have a banner made, prepare a feast and invite the whole village to be entertained. Speeches are delivered; first by the village elder, followed by a speech from me and then the last by the Minister. It shows we are working in partnership and the village elders are very important people in the process.

You said you have more than 500 Tagal sites, that’s a lot of rivers!

They are not all rivers. We now have extended the idea to artificial sea reefs, tidal estuaries, a sea cucumber colony and canals between paddy fields. And, some rivers have more than one village in the Tagal. We do sometimes have to step in to solve disputes between neighbouring villages.

Everywhere you get people living close to a natural resource you can introduce the Tagal system because it’s not just about harvesting the resource, it is also about finding ways to make income for the people who rely on the resource. We now find that some places allow catch-and-release angling, others only allow you to swim with the fish and take a fish massage, or in some you can pay to feed the fish only. Lots of people like to just throw in some food and watch the shoals of fish coming to them.

Then, because a lot of these schemes are in remote villages, you need accommodation for the visitors, so there’s another source of revenue for the locals. We try to encourage homestay, so it is small scale and sustainable. There’s no need to build big resorts, so it is good eco-tourism.

What do you feel about fish now?

I’ve learnt a lot about them through Tagal. I now know fish are very clever. I used to think fish were stupid, but they know where the Tagal red zone is and they all go to live there…

We sometimes get problems with African catfish and tilapia escaping from fish farms, and need to remove them before they get out of control. The best way is to send divers at night with lights and harpoons. The mahseer know they are safe and swim along with the divers but the tilapia and catfish all scatter because they know they are in trouble.

I really like to go fly fishing, but I am more respectful of the fish now. One time we were taking a fish to the lab for tests and I needed to kill it. It turned and looked at me and since that time, I know I cannot easily kill a fish. So, I am very happy to be protecting fish and encouraging catch-and-release.

Have you been back to England since finishing your degree?

Yes, I went back to Plymouth in 2011 – it had changed a lot!

When I was at university I would go to the fish market and buy the fish and sometime got free fish heads. The fish heads (salmon and cod) are delicious in soup but nobody in your country uses them. The fishmongers would say: “Is it for your cat?” I said “yes” and got them for free, otherwise they would throw them away.

When I was at university I would go to the fish market and buy the fish and sometime got free fish heads. The fish heads (salmon and cod) are delicious in soup but nobody in your country uses them. The fishmongers would say: “Is it for your cat?” I said “yes” and got them for free, otherwise they would throw them away.

While I was there I tried fishing for mackerel. Those fish were crazy, lots of them and easy to catch. It’s not like here where we have so many people fishing to eat and taking everything away.

What do you think the future holds for your schemes?

Soon, I will retire, I’m nearly 60 now. We get new officers working for the Fishery Department, many of them people from the Tagal villages who decide to work with fish, but not so many have the time to give to really be involved with a scheme like Tagal. It is proving troublesome to find a good successor.

My wife Marie is the Principal of St. Michael School in Kota Kinabalu and she has been winning awards for her environment conservation projects in the school. The recognition for her school has been with awards at local level, like the Sabah Most Promising Eco School, to national level with the Malaysian Sustainable Environmental School award and throughout Asian by winning the ASEAN Eco-School award. She is a scientist, and is helping to encourage the children in her school with this environmental conservation work which also includes rivers.

Then there is climate change, and that is a problem. We always had a rainy season and a dry season before and the fish would always breed at the start of the rainy season. Now we can get rain at any time, very heavy rain, and the fish can spawn at any time of year.

In the villages, they used to only harvest fish towards the end of the dry season, never in the rainy season when the fish were breeding. Now it is possible that they will harvest fish that are breeding and that could be a problem.

I hope other countries can use the Tagal scheme. In Sumatra there are some rivers where they have similar scheme. Sarawak State and Pahang State (on the Malaysian mainland) have adopted our Tagal scheme. I recently went to Cambodia to represent Malaysia at the International workshop on community-based fishery resource management in coastal waters and rivers. Hopefully Cambodia will begin using Tagal. I believe the Sabah Tagal system is one of the best systems, if not the best, in the region for protecting rivers, reviving the depleted river fisheries resource and then harvesting them in a sustainable manner.

I hope other countries can use the Tagal scheme. In Sumatra there are some rivers where they have similar scheme. Sarawak State and Pahang State (on the Malaysian mainland) have adopted our Tagal scheme. I recently went to Cambodia to represent Malaysia at the International workshop on community-based fishery resource management in coastal waters and rivers. Hopefully Cambodia will begin using Tagal. I believe the Sabah Tagal system is one of the best systems, if not the best, in the region for protecting rivers, reviving the depleted river fisheries resource and then harvesting them in a sustainable manner.

The Sabah Tagal system can be used throughout the world, why not?

Steve Lockett is Press Officer for the Mahseer Trust. He conducted this interview during his August 2014 tour of Indonesia and Malaysia, where he took samples from both captive bred and wild mahseer for further scientific study; engaged with local communities, scientists and anglers about mahseer and river conservation issues; worked with educators and the Malaysian government to promote angling as a conservation tool. This tour was made possible partly thanks to donations to the Mahseer Trust at a variety of events in the UK.

All images courtesy of Jephrin Wong