On Geoff Maynard’s beat the fields don’t just disappear beneath placid floodwater, they become part of the raging maelstrom with strong currents and roiling eddies; the salmon hut has avoided drowning by a mere 20 paces on more than a few occasions in recent years.

At these times it is all but impossible to imagine the tinder dryness of high summer; to believe that you will, again, stroll rod-in-hand through tall, yellowing grasses to the babbling flow at the beach. Under the leaden blanket of a winter’s day the oceanic valley seems all too permanent; something that will never recede; a condition you’ll have to live with.

But recede it does, and on returning to the river you find the most improbable changes brought about by the relentless, all-powerful surge of the previous week: shallows gouged to form formidable deeps of twenty feet or more; lengthy stretches of boulder-reinforced banks gone; brand-new gravel-runs; islands; sheer drops and new snags to fish to. It’s a whole new river every year and, frankly, it’s rather exciting. It presents new places to fish and with different methods. Where you would normally never consider fishing for, say, pike, you would now happily plot-up with a pair of dead-bait rods. Similarly, trout and grayling riffles exist where once the mean and moody glide would never have drawn you with a fly rod.

Among these phenomena is the silt-bank. Post flood, the long island at the head of Geoff’s stretch reveals a maze of fresh, sandy spits and promontories which we eagerly explore for new fishing opportunities. We duck and weave through willow branches finding freshly formed plateaus and bars from where we might position a bait in a previously inaccessible run of the main river.

As we plunder this new world so our cleated size10s violate the pristine sands of the shores, clunking-great boot-prints marking Man’s intrusion alongside the tracks of the gentler species: heron, moorhen, egret and various waders. Not uncommonly we’ll happen upon a series of otter or badger-prints; occasionally, those of a deer or, maybe, a fox. They are easily identifiable from both experience and the aid of a British Wildlife book with a section on animal-tracks. Birds of any kind are, of course, no problem. Neither are the footprints left by cloven-hoofed and clawed species like deer and badger, but what Geoff and I found in the late winter of 2013-14 took us aback somewhat…

With thanks to BBC Southern

Eager to reach a particular point without the need to splash through shin-deep water we stepped up and onto a natural ‘path’ through the undergrowth. We’d taken no more than a few paces when we found ourselves following the fresh and well-defined prints of something distinctly feline, so we stooped to examine them and to confirm our suspicions. They were those of a cat alright: a very large cat.

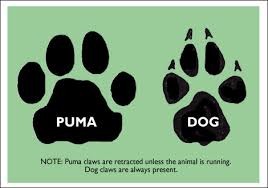

Now Geoff and I know the area well enough to know that domestic cats (and dogs) never, ever venture across the mile of open fields to the river – and a mid-stream island really isn’t the kind of environment a moggy would want to frequent at this bleak and dangerous time of year. Apart from any other consideration these prints measured 4” across and were found to tally exactly with images of puma prints found on Google!

With thanks to BBC Southern

Quite honestly, I don’t think the significance of this took hold of us until much later when every alternative had been considered and discussed. At the time, we were certain of the prints’ identity but couldn’t quite take on board the reality of a ‘Big Cat’ residing on our stretch of river – but take a look for your selves! I only wish the true significance of what we’d found had occurred to us at the time; we’d have procured a spade and cut-out the square foot around the print or, maybe, made a plaster-cast.

With thanks to the Auburn School

The photo is pretty good though, proof I think of a Big Cat’s presence in the Wye Valley…