We’ve had some really interesting discussion about cameras on the forum of late, and especially interesting to me because photography has always been one of my passions. It’s a great hobby to combine with fishing for our great sport often takes us to scenic locations and presents us with a variety of subjects.

The first question you should ask yourself The first question you should ask yourself is ‘what do I want a camera for?’ Yes, I know you want to take some pictures, including trophy shots of yourself with fish. But my question is more along the lines of, do you want a camera for viewing images on your PC and maybe for publishing pictures on the web? Or do you want it for viewing prints? Or for possible publishing in newspapers and magazines? It’s an important question because knowing the right answer can save you lots of money. Let’s first take a look at some basic facts about film and digital photography. Film There are large format film cameras but we are not concerned with those here. So the choice is between 35mm and APS (Advanced Photographic System). APS film is contained in an easy to use cassette that is quick and easy to load and unload and has more flexibility in the format (standard, wide and panoramic) it can produce. If you’re only going to want the usual standard size snap-shot sized print then an APS camera is plenty good enough. But if you want the occasional enlargement, and want the best quality print, then 35mm film is better, simply because it’s bigger. The bigger the negative the less the picture will degrade when enlarged. Prints are easy to carry around and show to your friends. Extra prints can easily be made if you want any. And if you want to view your pictures at a very large size you can use slide film instead and project the picture onto a screen or suitable wall. In spite of digital images now being on a par with film-based photographs as far as quality is concerned, many publications still prefer (insist in some cases) on transparencies for publishing, or at least on good quality prints from negatives. However, this is changing rapidly and where speed is concerned (news pictures for daily newspapers, for instance) the digital image is preferred. If you have leanings towards having your work published then always check out the preference of the publication you’re aiming for. Much depends, of course, on the newsworthyness of the shot. For instance, if you have a picture of a Martian just landing then they’ll use it if was taken on a Kodak Brownie with a dirty lens. Films have to be bought and then processing has to be paid for. If you’re a keen photographer this can add up to a considerable figure over a period. If you want to view the pictures within an hour or so then you have to find a processor and pay heavily for a ‘one hour’ service. If you have made a balls of a shot then it’s too late, the fish will have been returned or the moment lost. Storing and archiving prints, negatives and slides takes space and time, and finding a particular shot can be difficult to say the least unless you’re very well organised. Using film-based photographs on the Net or sending them by email means you have to get the prints or negatives scanned and turned into digital images. Digital Digital cameras don’t use film, they use a memory chip (Compact Flash and Smartmedia are the common ones) that have various capacities ranging from 8mb to 128mb or greater. The number of shots you can take is controlled by the available memory and the pixel size of the shots you’re taking. Once the memory is full you can then transfer the images to your computer’s hard drive, floppy disks, writeable CD, or other data storage device. Then delete the images from the camera memory and start all over again. Digital images are made up of anything from hundreds of thousands to millions of tiny dots or elements we call pixels and which we usually see written as 1 megapixel, 2 megapixel, 3 megapixel, etc, when one megapixel equals one million pixels. A computer and printer uses these pixels to display images or print photographs by dividing the screen or printed page into a grid of pixels. It then uses the values stored in the digital photograph to specify the brightness and colour of each pixel in this grid. Controlling the pixels in this way is called bitmapping and digital images are known as bitmaps. Most digital cameras store their images in a format known as JPEG, with a top quality format known as TIFF. The quality of a digital image depends on the number of pixels (resolution) used to create the image, and the quality of the lens on the camera which will greatly determine the colour, intensity and sharpness of the pixels. More pixels adds detail and sharpens edges. The more you enlarge a digital image the more you enlarge the pixels (eventually causing an effect known as pixelation), which eventually shows a degraded image, much the same as enlarging a film-based print when you enlarge the grain. The byte-size of a digital image is determined by the total number of pixels used to make up the image, ie, a quite low resolution image will be 600 x 400 (240,000 pixels), whereas a high-res image will be 2400 x 1600 (3,840,000 pixels), or more. You can print from a digital image using a computer and printer, but this is more expensive than film-based prints from the High Street shop and the quality isn’t usually quite as good. But if you have any special shots you want printing then you can have them printed professionally (there are a number of companies offering this service on the Net). Many digital cameras these days offer the option of being able to print direct from the camera. The big advantage to printing your own is that you only print the best ones, the ones you really want, rather than every shot on the memory card or on the roll of film. Viewing the images is easy, either on your PC or through your TV. Storage and archiving is equally easy by having the images burned to CD. Using the images on the Net or emailing them is easy, the only work required (usually) is to reduce them in pixel size to suit wherever they are being used. Most digital cameras come with software for image management, including image cropping, enhancing and sizing (pixel reduction). Film still has the edge on convenience and price if you want to walk around with an envelope full of snap-shots to show your friends. But even this is rapidly becoming more affordable and convenient with digital images as ‘snap-shot’ printers and media come down in price. Film is definitely on its way out. It will be a while yet, but the writing is very clearly on the wall. Cameras The price of any camera is generally based on the quality of the lens, the number of features and, in the case of digitals, the number of megapixels it can take. Most features are designed to make picture taking easier, but not necessarily better quality. Nearly all cameras have an ‘automatic’ function where the camera works out all it needs to know (aperture, shutter speed, focus, flash/no flash) to take a good shot, and these days the auto setting is pretty foolproof. The best cameras have a manual mode so that the photographer can make creative settings and adjustments.

Compact cameras are those that have a viewfinder, where you look through a window that gives you a fairly accurate replication of what the camera lens is seeing. Some have a fixed lens, usually 35mm in focal length, which is a good focal length for general photography to give you a fairly wide view and a decent depth of field (the range in a picture that remains in sharp focus). Zoom compacts have an adjustable lens which varies the focal length, usually from 35mm to 80mm. SLR cameras have a viewfinder that actually looks through the lens (TTL). This is a major advantage when framing shots and especially when taking close-ups due to what is known as ‘parallax error’. Put simply, parallax error means the discrepancy between what the viewfinder sees and what the lens sees, which is more pronounced the closer you are to the subject. Digital cameras get round this by allowing you to view the scene through a small LCD monitor of the view through the lens. The disadvantage of SLR’s is that they need a complex system that lifts the mirrors clear of the lens in that fraction of a second the exposure is made. This is part of the reason why, generally speaking, SLR’s are more expensive than their compact equivalents. SLR’s usually come with a zoom lens and have a wide range of interchangeable lenses available as optional extras. They are also much heavier and bulkier. Digital SLR’s are still very expensive and usually come as body-only. Each type has a price range which means that the most expensive compacts can cost more than the cheapest SLR’s. The quality of the lens and (in the case of digitals) the number of pixels it can take, is usually the decisive factor. Making the choice Okay, film or digital? If all you want is standard size snap-shots to carry around and show your friends then, for the time being at least, stick to an APS or 35mm film camera. A compact costing less than £ 75 is plenty good enough. If you want big enlargements from those shots then pay a bit more, £ 100-plus, for a compact with a better lens.

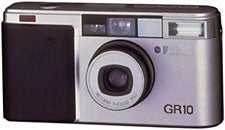

Most anglers will need nothing better than a digital camera costing about £ 300. Do your homework, read all the reviews anywhere you can find them. Buy a digital photography magazine, and go for the camera that has the best lens in the price bracket you’ve opted for. When you’ve narrowed that down to a choice, then go for the camera that delivers the most pixels in that bracket. You only need a better digital camera if you have hopes of having images published in newspapers or magazines, and even then it depends on which publication for some will accept lower quality images than others. Obviously I can’t cover everything about format and camera choice in one article, so I’ve tried to cover the most important points. I still have a lot to learn about digital imagery and no doubt some readers will have a different idea to me about some of the aspects I’ve covered. I don’t profess to be an expert, but I have used a digital camera for several years and have learnt quite a lot in that time. What I use The 35mm cameras I use are a Ricoh GR10 compact which I carry with me all the time for trophy shots. And a Canon EOS 50E SLR for those times when I need to take a greater range of pictures for a magazine feature. I use Fuji Velvia and Sensia slide film. I upgrade my digital cameras on a regular basis (for personal and for tax reasons) and have used quite a few in the past five years. My first one was an Agfa (can’t remember the model name) and compared to what I use today it was very poor, in both pixel and lens quality. Then I went through two Epsons, which were noticeably better. In fact, for web work they are still plenty good enough.

The 6900Z is a proper camera shape and we’ve taken some first class shots with it. It has a multitude of bells and whistles but I was mainly attracted to it because it is a pseudo SLR. Not a true SLR for the image in the viewfinder is just another tiny LCD screen like the one on the back, and it was this that eventually put me off it for the image in the viewfinder is not as good as a true optical view – that and the fact that the taxman will be wanting a slice of my income very soon. So where could I go from a Fujifilm 6900Z, which is one of the best digital compacts (SLR shape) on the market? How could I go better without going to the expense and bulk of a true digital SLR? After all, isn’t the 6900Z a six megapixel camera, which is as big as you can get currently? Yes and no. It may surprise some digital camera fans to know that their supposedly six megapixel cameras (the 6800Z and 6900Z, amongst others) are only a true 3.3 megapixel. Fujifilm uses its own version of a process known as interpolation (resampling), which means that the camera is using internal processing algorithms to generate it’s true 3.3 megapixel CCD to a 6 megapixel image. The bottom line is that the camera captures 3.3 million distinct pixels, not 6 million. But let’s be fair about it, the result from this interpolation is still very good indeed. Fuji digital cameras still produce some of the best digital images I’ve seen in their class. But you still can’t escape the fact that, in spite of the Fuji method of interpolation being the best there is, you can’t create detail you didn’t capture in the first place. When the Fujifilm 4700Z was first announced it was released as a 4.3 megapixel digital camera, and only later did it emerge that the camera had only a 2.4 megapixel CCD and Fujifilm were forced to remove the 4.3M labels from the front of the cameras. So the only route I had was to buy a compact digital camera that gave me more ‘true’ megapixels. I chose the Olympus Camedia C4040 Zoom, which has 4.1 megapixels and the fastest (f1.8) lens on the digital compact market. It also has an infra-red remote control which is extremely useful to an angler. The C4040 has recently been superceded by the C5050, the details of which I don’t yet have, but it still uses the same f1.8 lens, so it is probably only a cosmetic model change. I found the cheapest price on the Net, which at the time was £ 549, made sure they’d got it in stock, printed off the ad, and then bought the camera from my local Jessops who have a price matching deal. All I can say is that this Olympus is giving the best quality digital image I’ve seen from any compact digital camera. The lens is a real top quality job. To get this superior image I’ve sacrificed (in the Fuji 6900Z) some zoom power and a couple of other features, but not anything I’ve truly missed. Writing about interpolation has reminded me that there is another thing to be wary of – digital zooms. The only zoom factor worth having is the optical zoom, this is 3X on most digital compacts, although the Fujifilm 6900Z has a true 6X zoom. Most digital compacts have a digital zoom facility that ‘apparently’ increases the zoom by as much, in some instances, of 10 times. All a digital zoom does is enlarge the pixels, which you can do just as easily in the software that came with your camera by cropping an area and then enlarging it. In both cases the enlarged pixels simply become pixelated, grainy in film terms, and the image is excessively degraded. Loads of other features There are loads of other features on digital cameras that I haven’t even mentioned. Many of them you’ll never use, for the bog standard ‘auto’ setting will make a top job of 99% of the images you’ll take. Many cameras will take MPEG video and record sound, have USB connections, etc, etc, etc. The most important features are megapixels, lens, how the power is supplied (type of battery, etc), comfortable handling, decent flash, timer or remote facility for taking self-portraits, and a good range of accessories. Recommendations There could be better cameras on the market than the ones I’ve used, but of those I’ve personal experience of I would say the choice is between Fuji and Olympus. Decide what you want a camera for, decide how many megapixels you need, study the features that each model offers, compare prices, and then, before you part with your cash, handle the camera in the shop. Buy used only if you know the person you’re buying from, or from a shop if it carries a decent warranty. If you’re still unsure, want more details or opinion, then come onto the forum and ask. |

Welcome!Log into your account