You may not be aware that the long, green, slimy, tackle-tangler we tend to curse – otherwise known as the European eel – is in massive decline.

Of course, there are those who love catching anguilla-anguilla, to give it its Latin name but, Frankly, I hate hooking them. Invariably, they cause all sorts of problems with your end tackle, knitting it into something unrecognizable from what you originally tied up – and there’s always that slime!

I spelt ‘Frankly’ with a capital ‘F’ because I do remember one night when Frank Guttfield and I were fishing and he’d just returned a nice little barbel of around 6 lbs. On the very next cast his bait was instantly taken and he thought he was into another barbel only to find an eel when it eventually surfaced. I grabbed his landing net again, but this time he said “Don’t use my net, use yours” and without thinking I exchanged his landing net for mine. After he returned it I asked “why my net?” to which he simply answered “Well, just look at the state of yours now!” S-l-i-m-e-d!

Neither of us liked catching eels but we both appreciated the contribution they make to our riverine species – and lakes too, of course. They seem to get everywhere and many think that the stories of them travelling overland on moonlit nights is bunkum, but I’m still not convinced. How do they get into lakes that are sometimes miles away from any river? Another of those mysteries the eel poses…

And mysterious they are! Surprisingly little is known about their breeding and spawning habits and what is causing their decline. Some say a fluke that gets into the eel’s gut is to blame, but surely something like that would have gone on for centuries? Is it pollution or overfishing for them? Well, back when eels were extremely popular to eat, eel pie or pie and mash as it’s referred to, was the staple food in the East end of London. It was also a delicacy for many of the upper class and often rents were collected in numbers of eels. The business was huge with hundreds of tons being caught and traded so, if overfishing was the problem, surely their decline would have been noticed back in Victorian times? And of pollution, think of the Thames and the ‘Great Stink’ of the 1850s, yet tons of eels were still caught in the Thames and further upstream.

This decline has occurred since the 1950s and especially so in the last 30-40 years where the number of glass eels has reduced by around 90%, such that in 2008 it was classified by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as Critically Endangered on the red list. That’s not just eels in British rivers, it’s all across Europe. In 2007, the European Commission Regulation (EC no. 1100/2007; EC 2007) ‘Establishing measures for the recovery of the stock of European eel’ was enacted. It required Member States to develop mandatory Eel Management Plans for their river basin districts (RBD)

Right now, it’s illegal for anglers to land and remove an eel for the table or any other purpose; they must all be returned immediately. Yes, there are still licenced netsmen out there, but they only now take around 8 tonnes of British eels (that’s still maybe 8,000-12,000 eels that will never have the chance to spawn again.) The remainder of the British demand is shipped in from Europe, so the problem of overfishing on the European mainland continues.

So that then raises the questions: when the eels get back to the Sargasso Sea where they spawn, do their offspring return to the same river their parents grew up in? And do French eels interbreed with British or Swedish eels? The fact is, no one knows. All they do know is that European eels do not interbreed with American eels that use a similar spawning territory, but it seem these species keep well apart.

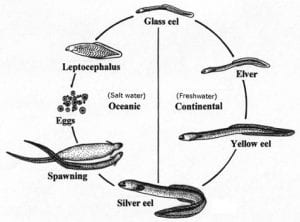

The life cycle of the eel.

After spawning, the eggs hatch and the first stage is leptocephalus, whereupon they start to drift across the Atlantic, a journey taking 6-9 months. They arrive as ‘glass eels’ and, upon entering the river systems, transform into ‘elvers’, the first stage of the yellow eel. As they migrate upstream and grow they remain as yellow eels and this is how we normally catch them in our rivers and lakes.

Glass eels

One of the barriers they face in our rivers is the weir. These are solid structures and few are fitted with suitable passes that eels can utilise. This is where I got involved and I’ll go into that later.

Upon maturity, they will head back downstream where they transform again ready for their great sea journey into silver eels. All the eels from across Europe then swim down to the Azores then across the Atlantic for their final journey to the Sargasso Sea. During daylight they’ll swim at depths of up to 600ft to avoid predators while at night, when there’s less danger, they’ll come up to 100ft.

Predation at sea is, perhaps, one of the biggest obstacles for eels, so turning silver must help in reducing predation. Radio tracking devices have been placed on a number of eels but they’ve only been tracked as far as the Azores; beyond here the devices are either lost or consumed by sharks or other predators – along with the eel.

Very little is known about their spawning habits on reaching the Sargasso Sea: what depths and what types of environment do they prefer?

British monitoring.

As mentioned, weirs are a major problem for eels. There’s no way for them to get over large concrete structures and even modern fish-passes, Lariniers for example, are of little use. The salmon ladders installed on Thames weirs back in the early 80s are even worse, most being based on the older Denil or baffle-pass designs. The ideal pass for an eel is a tube or brush-lined trough through which eels can navigate their way to the top.

Somewhere along the pass or at the top is a trap where the eels can be comfortably held and counted until their planned release.

An eel-pass

There are quite a number of these traps now in use in the Thames River Basin District (RBD) where they are monitored by volunteers as part of the ‘Citizen Science Monitoring Scheme’. This was started by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) in 2005 and greatly improved in 2011. Members are termed ‘Citizen Scientists’ (CS) and are trained to collect and process the data as part of a scientific investigation.Eels shorter than 120 mm are classified as ‘elvers’. Those equal to or longer than 120 mm are recorded as ‘yellow eels’. Where greatly more than fifty eels are recorded, a sub-sample of fifty are randomly selected and measured to provide a representative sample of all the eels trapped on that occasion. Following measurement, eels are released back into the river at the margin upstream of the barrier. To avoid large eels being handled, those exceeding 300mm are released without measuring and recorded as >300mm.

In 2014 a record number of 45,948 eels were counted (since counting began) and hopes were raised that the eel was at last making a come-back. Sadly, the eel counts in 2015 were back down to 22716 and 23,095 in 2016 so concerns for their future are not yet over. A point to note is that there will always be some variation in the counts at the various sites from year to year, but the general trend is steady.

So how did I get involved?

It was three years ago that Darryl, the EA Fisheries Officer with responsibility for eels, came to an ATTRF meeting and gave a talk about these mysterious fish. He told us how weirs were their greatest obstacle and how eel-passes would help them. Coincidentally, we had the Thames Valley Police Diving Team practising in our weir at about the same time and they told me there were literally thousands of eels along the sill of the weir.

When you put 2 and 2 together you often come up with more than 4 and I was motivated me to ask Darryl to visit the weir. He pointed to an area by a riverside hotel where, with permission, a pass could be fastened to their wall and equipped with a trap. Could we find some volunteers to empty the trap each week and count the eels as part of the data collection? The answer to that was ‘yes’ but three years on and the EA still hasn’t found the money for the pass – let alone the trap as well, a total of around £5000, so for some time now I have been looking for someone to sponsor the pass and the trap. However, we’ve since realised that a trap may be impractical at this weir and that a better site exists so the cost may now only be around £3000.00 – but I’m still looking!

The Eel Forum

In the meantime, my contact at Thames Water suggested I contact Joe Pecorelli at ZSL and he then invited me to join in the Eel Forum. We now have all the contacts in place and I’m just looking for the money. I may in the end ask the hotel; it’s nothing to them and they can hang their name on it as a bit of publicity. I’m not bothered so long as we get the pass in place! It’s either that or I will have to twist Thames Water’s arm once again.. They are very generous like that.

(Note: This is my personal opinion, no one else’s. Just as a point of interest: you won’t need much reminding of the fine Thames Water recently incurred in their pollution cases, but what wasn’t made clear was the EA’s successful claim of over £600,000 for legal fees. This alone would have put an eel pass on every Thames weir as far as Lechlade and quite a few of the weirs on the tributaries too. Just putting things into perspective, but I’m sure the legal team will spend their winnings wisely. That’s my bit of sarcasm over)

The future for eels

Presently, it’s looking grim. We need to ensure their unhindered migration up and down the river systems through eel passes. We also need to immediately STOP eating eels: kill the demand and you kill the trade. As anglers, whether we fish for eels deliberately or accidentally, we need to do so with care and ensure they are returned in good shape to healthy waters.

Who knows? One day there might be a resurgence in their numbers. Let’s hope so because a river without them is unthinkable.

Jeff Woodhouse

(Many thanks to the EA’s Darryl Clifton-Dey and ZSL)